In this page -----

1- Introduction 2- Issuese of Concern 3- Cellular Level

4- Development 5- Organ systems Involved 6- Function

7- Related testing 8- Pathophysiology 9- Clinical Significance

(1)- Introduction --

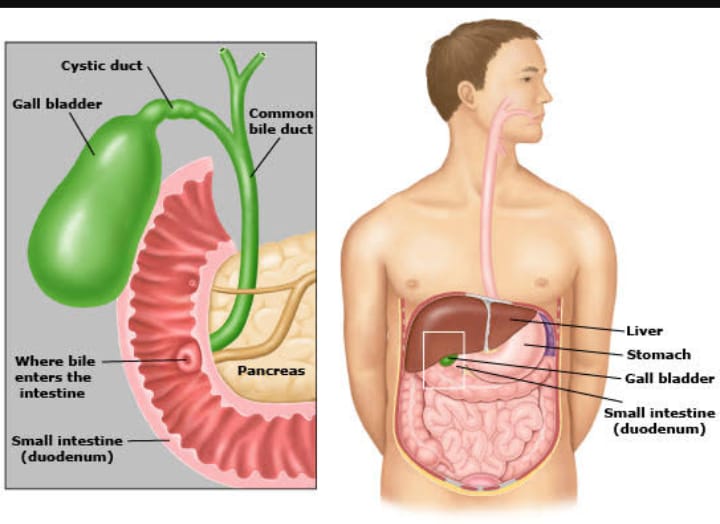

The gallbladder is a small hollow organ about the size and shape of a pear. It is a part of the biliary system, also known as the biliary tree or biliary tract. The biliary system is a series of ducts within the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas that empty into the small intestine. There are intrahepatic (within the liver) and extrahepatic (outside of the liver) components. The gallbladder is a component of the extrahepatic biliary system where bile is stored and concentrated. Bile is a fluid formed in the liver that is essential for digesting fats, excreting cholesterol, and even possesses antimicrobial activity. The gallbladder lies in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen affixed to the undersurface of the liver at the gallbladder fossa. It is attached to the rest of the extrahepatic biliary system via the cystic duct. The liver produces bile that is drained into the gallbladder and stored until needed for digestion.

(2)- Issues of Concern --

Dysfunction in the physiology of the gallbladder most commonly results in the production of gallstones. Imbalances in the constituents of bile and biliary sludge secondary to gallbladder hypokinesis can lead to the precipitation of insoluble stones. When these gallstones cause physical blockages in the biliary tree and beyond, pain, inflammation, and infection can result in damage to the gallbladder and a host of other organs. Many gallbladder pathologies will ultimately warrant surgical intervention, and thus cholecystectomy, or removal of the gallbladder, is one of the most common surgical procedures performed in modern times.

(3)- Cellular Level --

The liver is a large organ located in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. It is composed of hepatic lobules which are hexagonally shaped functional units of the liver. These lobules are mostly composed of hepatocytes, or liver cells. Hepatocytes have many important functions including the production and secretion of bile. Hepatic lobules also contain a central vein and portal triads at the periphery consisting of branches of the bile duct, portal vein, and hepatic artery. Epithelial lined sinusoids run between the hepatocytes and connect the peripheral vasculature to the central vein. The bile produced by the hepatocytes is drained in the opposite direction of blood flow to the periphery of the lobule by small channels known as the Canals of Hering. They are lined by simple cuboidal epithelium and ultimately drain the bile into the bile ductule of the portal triad, which will go on to drain into the bile duct.

The gallbladder wall is composed of several layers. The innermost mucosal layer is made up of columnar epithelium with microvilli. The microvilli increase surface area which is useful for concentrating bile. Beneath the mucosa is a lamina propria, a smooth muscle layer, and an outer serosal layer due to its intraperitoneal location.

(4)- Development --

The gallbladder and biliary system develop from the foregut. By the end of the fourth week of embryogenesis, a structure called the hepatic diverticulum appears. The hepatic diverticulum goes on to become the liver, extrahepatic biliary system, and a portion of the pancreas. The superior bud of the diverticulum develops into the gallbladder. At week six, the common bile duct and part of the pancreas rotate around the duodenum. The bile ducts undergo plugging with epithelial cells and recanalization of their lumens, with the common bile duct and cystic duct connecting by week seven. By week twelve, the gallbladder is no longer solid and the liver is secreting fluid through the patent bile ducts that now empty into the duodenum. The development of the biliary system is extremely complex and can lead to numerous variations in its structure.

(5)- Organ Systems Involved --

Related organ systems that affect gallbladder physiology include the small intestine, pancreas, and the liver. Bile is formed in the liver which is then stored and concentrated in the gallbladder. Stimulation of the small intestine by fatty foods and proteins causes the gallbladder to empty the bile into the duodenum. The cystic duct drains the gallbladder and connects with the common bile duct. The common bile duct continues on to merge with the main pancreatic duct at the ampulla of Vater in the pancreas. A gallstone that becomes lodged in the ducts in the pancreas is a leading cause of pancreatitis. A cholecysto-enteric fistula, or an abnormal connection between the gallbladder and intestines, can lead to a rare form of small bowel obstruction.

(6)- Function --

The function of the gallbladder is to store and concentrate bile, which is released into the duodenum during digestion. Bile is an alkaline fluid continuously produced by the liver whose primary function is to aid in digestion and absorption of lipids, as they are not soluble in water. It is composed of cholesterol, bilirubin, water, bile salts, phospholipids, and ions. The cholesterol excreted into bile eliminates most of the cholesterol in the body.

Specialized enteroendocrine cells called I-cells are located in the duodenum and jejunum. When these cells are stimulated by fatty acids and amino acids released from the stomach, a peptide hormone called cholecystokinin (CCK) is released. CCK has two main functions pertaining to the gallbladder. Its first function is to stimulate the smooth muscle of the gallbladder to contract and release bile into the biliary tree. The second function of CCK is to simultaneously signal the muscular sphincter of Oddi to relax. After leaving the gallbladder, bile flows down the common bile ducts into a confluence with the main pancreatic duct called the ampulla of Vater. From there, it travels through an opening called the major duodenal papilla into the second portion of the duodenum. The flow through the papilla is controlled by the opening and closing of the sphincter of Oddi. When not stimulated by CCK, the gallbladder relaxes and fills with bile. Outside of the gallbladder, CCK stimulates pancreatic secretions necessary for digestion and delays further emptying of the stomach. Release of CCK is inhibited by the hormone somatostatin which functions to turn off digestion.

Bile acids are synthesized in the liver from cholesterol precursors. The rate-limiting step of bile acid production is catalyzed by cholesterol 7α—hydroxylase. The bile acids are conjugated to the amino acids glycine and taurine and become soluble bile salts. These bile salts are important in the process of emulsifying lipids in the intestine. As the lipids are metabolized into free fatty acids and monoglycerides in the digestive tract, they are then packaged into micelles made up of bile salts that act as surfactants. Bile salts are able to do this because of their amphipathic nature. Their hydrophilic portions interact with water making them soluble, while their hydrophobic portions keep lipids contained in the center. The hydrophilic portions are also negatively charged, which repels them from other bile salts and keeps the lipids small and easy to digest. Cholesterol and phospholipids are also contained in the structure of the micelles. The bile salts are reabsorbed in the distal ileum of the small intestine and recycled back to the liver in a pathway called the enterohepatic circulation.

Bilirubin is a yellow pigment that is produced as a breakdown product of heme contained in red blood cells. This compound is initially unconjugated and insoluble in water. The unconjugated bilirubin, also called indirect bilirubin, is taken up by the liver and conjugated with glucuronate via the enzyme UDP-glucuronosyltransferase. The then conjugated bilirubin, also known as direct bilirubin, is then excreted into the bile in a soluble form. The bilirubin contained in bile will eventually travel through the gastrointestinal system and give urine its yellow color and stool its brown color via the breakdown products urobilin and stercobilin, respectively. If bile is unable to enter the duodenum, the buildup of bilirubin leads to jaundice, which is the yellowing of the skin, eyes, and mucus membranes, as well as acholic (pale) stools.

(7)- Related Testing --

The initial test of choice to diagnose most disorders of the gallbladder is an abdominal ultrasound. This is a noninvasive test and can effectively evaluate the gallbladder for stones, sludge, and signs of inflammation. X-ray is less sensitive, as calcified gallstones are only seen on plain abdominal x-rays in about 10% of patients with cholelithiasis. Often a CT scan is done during an emergency department visit to evaluate abdominal pain. This is very accurate when diagnosing gallbladder disease but exposes the patient to radiation. The most sensitive and specific diagnostic test to confirm cholecystitis is the hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan, also known as cholescintigraphy. This is a radionuclide scan where a tracer is given intravenously and is taken up by hepatocytes in the liver. The tracer then concentrates in the gallbladder if the cystic duct is patent. It is typically performed in the setting of an equivocal abdominal ultrasound with clinical suspicion of gallbladder pathology. CCK can be administered to test for the ejection fraction (EF) of the gallbladder. An EF below 35% is considered abnormal and indicative of functional gallbladder disorder. [11] A complete blood count (CBC) and a complete metabolic panel (CMP) are likely to be ordered in the setting of suspected acute gallbladder disease. An elevated white blood cell count, or leukocytosis, would be expected in the setting of inflammation. Depending on where a gallstone is located, various enzymes can be elevated. This includes the liver enzymes aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and the pancreatic enzymes lipase and amylase if the pancreas is obstructed. Additionally, bilirubin may be elevated. If gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) is ordered, it is likely to be elevated as it is found in both hepatocytes and epithelial cells of the gallbladder.

(8)- Pathophysiology --

(1)- Cholelithiasis and Biliary Colic -

Cholelithiasis is the term for gallstones in the gallbladder. The stones form as a result of imbalances in the constituents of bile and in situations of biliary stasis, which is a state where bile is not flowing. Gallstones are usually classified as cholesterol stones or pigmented stones. Cholesterol stones account for approximately 80% of stones. They are most often associated with the risk factors remembered by the 4 F’s: female, fat, fertile, and forty. This means that estrogen, obesity, multiparity, and advancing age are all risk factors. Pigmented stones are broken down into brown and black stones. The black stones are composed of calcium bilirubinate and are more likely to be seen on radiography. These stones are often secondary to pathologies that cause hemolysis, which is red blood cell (RBC) breakdown. The metabolized heme from RBCs causes the increased concentration of bilirubin in bile. Brown stones occur secondary to infection. While gallstones are normally asymptomatic, a person affected by cholelithiasis may experience something called biliary colic if a stone becomes lodged in the cystic duct. Biliary colic is characterized by right upper quadrant pain in response to fatty meals, as the lipids stimulate the secretion of CCK which causes painful contractions against the stone.

Choledocholithiasis occurs when a gallstone becomes lodged in the common bile duct. The effects of the lodged stone and subsequent changes in laboratory values are determined by the stone’s location. If the stone has not traveled far, liver enzymes such as ALP, GGT, AST/ALT, and bilirubin are likely to be elevated. If the stone has traveled far enough to reach the pancreas, amylase and lipase will become elevated as a result of pancreatitis.

(2)- Cholecystitis -

Cholecystitis simply means inflammation of the gallbladder. This is most commonly due to gallstones in the cystic duct, termed calculous cholecystitis. Anytime a duct is obstructed, the resulting stasis can lead to inflammation. Compared to biliary colic, acute cholecystitis will likely cause prolonged abdominal pain with associated fever and leukocytosis. The feared complication of untreated acute cholecystitis is infection. Besides infection, chronic cholecystitis can occur if the gallbladder undergoes repeated attacks of acute cholecystitis. The resultant scarring and calcification increase the risk of cancer.

Another type of cholecystitis can be seen in critically ill patients without gallstones, termed acalculous cholecystitis. This can occur as a result of infection, low perfusion, or biliary stasis.

(3)- Cholangitis -

Cholangitis is an inflammation of the bile ducts. Most commonly this refers to ascending cholangitis, which is secondary to infection. If the biliary tree becomes obstructed the resulting bile stasis can lead to bacterial overgrowth. There is a triad of symptoms called Charcot triad that characterizes this type of cholangitis. The triad is jaundice (due to elevated bilirubin), fever, and right upper quadrant pain. If the patient shows signs of shock and altered mental status, the collection of signs is then called Reynolds pentad.

(9)- Clinical Significance --

Disruption of the gallbladder's normal physiology can result in a significant medical burden. Over 20 million Americans suffer from gallbladder disease and cholecystectomy is one of the most common surgeries performed. Many factors increase the risk for gallstone formation and gallbladder disease, with an increasing incidence as a person ages. Women are at a higher risk, accounting for about 14 million of the cases in the United States.

Knowledge of gallbladder physiology can aid in the prevention, understanding, and treatment of gallbladder disease. In clinical practice, patients can be counseled on weight loss as obesity is a risk factor for gallbladder disease. Those who have been discovered to have asymptomatic cholelithiasis can be educated on the importance of low-fat diets to decrease the incidence of biliary colic. There are many drugs that may increase the risk of gallstone formation and knowledge of these underlying mechanisms is important. For example, hormone replacement therapy containing estrogen causes increased levels of cholesterol. Somatostatin analogs such as octreotide block the release of CCK and lead to the formation of biliary sludge. Fibrates block the rate-limiting enzyme 7-alpha-hydroxylase causing increased cholesterol and decreased bile acid production. Knowledge of these mechanisms has also led to the production of drugs that can make a positive impact on a patient’s health. An example is bile acid sequestrants that prevent reabsorption of bile acids in the ileum and lead to lower cholesterol levels as the body is forced to use it as a substrate to produce new bile acids. In addition to drug side effects, providers treating patients who are undergoing prolonged periods of fasting or receiving total parenteral nutrition now appreciate that their patients are at increased risk biliary stasis due to the decreased stimulation of CCK.

Today, most cholecystectomies are performed laparoscopically as an outpatient procedure. This procedure affords a very low complication rate with a fast recovery. Despite this, expected intraoperative risks such as perforation and bleeding still exist. An uncommon complication termed post-cholecystectomy syndrome can occur postoperatively as persistent abdominal pain despite the surgery. As we garner further understanding of the pathophysiology behind gallbladder disease, more approaches can be taken that are focused on prevention to minimize morbidity and healthcare expenditure.

2023 © DL NEWS. All Rights Reserved.